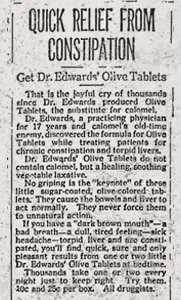

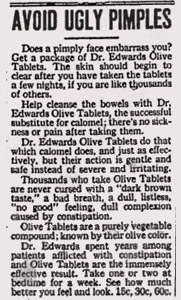

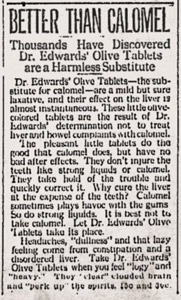

Above: Dr. Edwards' Olive Tablets advertisement from 1918. Advertising was exceedingly important to patent medicine makers and the Olive Tablet Company advertised profusely. |

Frank Mott Edwards, was born in 1865, in the small Lawrence County, Ohio village of Southpoint. Edwards attended the Miami Medical College in Cincinnati. Upon graduation in 1895, he returned to Southern Ohio and set up practice in Portsmouth. Buoyed by brick-making, iron and steel, shoe-making, and the railroads, Portsmouth was a bustling city of 50,000 and a great place for a young doctor to start out. As a doctor, Edwards encountered many cases of constipation and had been instructed in college about the dangers of auto-intoxication. Calomel (mercurous chloride) was at that time a favored treatment. It was effective but produced a violent, explosive, and often painful purging of the bowels. It was also poisonous. Frequent users could lose teeth, hair, jaws, become paralyzed, go insane, or die. Edwards sought a gentler and less toxic solution to his patients' woes. He compounded a pill of aloe, Jamestown weed, mayapple root, cascara bark--all substances known for their laxative effects--and olive oil. The pills seemed to have the desired effect for his patients. It was the Golden Age of patent medicine. Patent medicine sales exploded in the 1900-30 period—despite attacks by science, journalists, and the first stirring of regulation in 1906. Noting the fortunes others were making and the national obsession with constipation, Edwards began advertising and offering his laxative for sale. Dr. Edwards' Olive Tablets were first sold around 1909. Edwards' pills began to sell and sell well. The Olive Tablet Company became his principal business. The company was initially operated out of the doctor's hometown of Portsmouth but this quickly became unworkable. |

|

| In 1911, the doctor moved his business to Columbus, initially setting up in a building on Gay St. downtown. Columbus was already home to patent medicine giant Peruna and had the infrastructure and skilled workers Edwards needed. The city's excellent rail connections and location within 500 miles of over half the American population also recommended it. The business kept growing and soon the Gay St. premises were too small. In 1920, the good doctor had a building constructed expressly for his business. It was located on the city's north side, near the intersection of N. High and Fifth Ave. The building still stands today: |

||

The Olive Tablet Company building at 29 E. 5th Ave. |

||

| As for the doctor, he, his wife Alberta, daughter Virginia, and son Frank moved into a substantial home at 200 E. 14th Ave. (no longer standing, site is now a parking lot) in the University District. As his fortunes grew, he bought a larger, grander home at 131 E. 15th Ave. (torn down in 1939 to make way for the Delta Gamma Sorority House) where he spent the rest of his life. The 15th Ave. house was among the finest in the city and boasted a garage as big as many homes. The increasingly wealthy doctor later added a winter home in Miami Beach, Florida. | ||

|

The key to Edwards' fortune and that of the other patent medicine moguls was advertising. Edwards advertised constantly and prolifically. From the big city journals to the small town newspapers to the popular magazines of the day, from Atlantic to Pacific, an issue didn't go by without an ad for Dr. Edwards' little green pills. Advertising for Olive Tablets emphasized their gentleness and contrasted them with the horrors of calomel. The ads were firmly based on the auto-intoxication theory and promised to cure constipation along with a stable of other problems. Bad breath, pimples, bad complexion, headaches, a disordered liver, and lack of energy all fell before the power of the doctor's mighty pills. Readers responded to the ads. The ads told them what they wanted to hear. Safe, gentle, overnight relief of their distress was possible for just pennies. A caring, kindly, small town doctor from Ohio had concocted it from nature’s ingredients known and used for thousands of years. No need to risk the horrors of autointoxication when just two, small, inexpensive, pleasant-tasting pills could solve the problem. |

|

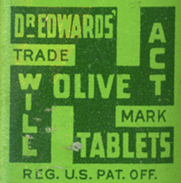

On each and every tin of Dr. Edwards' Olive Pills was a dark green swastika. Why this was has been lost to history. Prior to the Second World War, the swastika was a widely used and completely inoffensive decorative element. Its presence on Dr. Edwards' tins might have been an attempt to connect his product with the herb lore of the Native Americans or perhaps the secrets of exotic India or mystic Tibet. All three cultures made use of the swastika in their iconography. Patent medicine makers frequently tried to associate their product with the wisdom of ancient or exotic peoples. The rise of the Nazis in Germany after 1933 made the swastika untenable as a trademark. In 1934, the company altered the swastika on its packages by removing the left and right arms but by 1936 even this was stricken and the product's new logo became a line drawing of Dr. Edwards. |

|

|

The bane of Dr. Edwards's existence was the American Medical Association. Beginning in 1905, the AMA mounted an aggressive attack on patent medicines. It was enough of a problem that Edwards’ No. 2 at the company also served as president of the Proprietary Association, a trade group dedicated to fighting criticism, bad publicity, and regulation of the industry. As patent medicines went, Olive Tablets were far from the worst. They made modest claims. They did what they promised. They weren't filled with narcotics, poison, or alcohol like others. The great secret of Dr Edwards’ Olive Pills--revealed by the AMA in a 1913 exposé (Journal of the American Medical Association, vol. 60, no. 18, May 3, 1913)--was that, despite their olive green color and olive packaging and references to oil and lubrication, they contained no olive oil and--even if they had--the amount would have been so tiny as to not matter. Laxatives like Edwards Olive Tablets were not completely benign, however. Excessive or long-term use of laxatives and purgatives damaged the colon. Constant laxative users became dependent on them and unable to have a normal bowel movement. Some laxative users also developed a psychological addiction. On July 31, 1931, Dr. Edwards died of a heart attack in his University District home. He was buried back in southern Ohio. Edwards’ son took over operation of the company. Despite the discrediting of the doctrine of auto-intoxication and an easing of America's constipation anxiety, the firm soldiered on through the 1930s and 1940s. The company directed its attention to the female market and promoted itself as "The Laxative of Beautiful Women." In 1957, as the younger Edwards was nearing retirement age, the company was sold to consumer products giant Plough, which closed the local factory and moved production to Memphis, Tennessee. Plough eventually dropped the Olive Tablets and sold the product to a small firm called Oakhurst that specializes in traditional remedies. In a reformulated version, Dr. Edwards’ Olive Tablets are still available today. |

|

|

||

|

||