THE METHODIST MISSIONS CENTENARY, A World's Fair of Methodism (1919) Airplanes and dirigibles, exotic animals, fireworks, live stage shows, a carnival, parades, a Wild West show, a 100 piece all-trombone choir, and a gargantuan 150' tall movie screen don't sound much like Sunday School but that was the scene when Methodists staged a month-long world's fair at The Ohio State Fairgrounds in the summer of 1919.

|

|||

WHY THE CENTENARY? 1919 marked a century since the first Methodist missionary outreach. Back in 1819, John Stewart entered the still half-wild Ohio country to preach the gospel to Wyandot tribesmen near Upper Sandusky. Since then, American Methodist missionaries had penetrated into nearly every part of the globe. 1919 saw a world transformed. The Great War had toppled centuries-old empires and autocracies. America had emerged as a world power. Drunk on their own wartime propaganda, Americans imagined a global conversion to democracy and American values. Methodists believed the new world needed to hear their teachings. Methodists also saw the threat of atheistic Bolshevism growing out of the Russian Revolution and felt the need to confront it. 1919 saw colonialism at its peak with most of Africa and Asia subject to the control of one European power or another. Centuries-old barriers to the spread of Christianity were gone. At the same time, modern transportation and communication had expanded the potential reach of evangelism as never before. Methodists felt a duty to sieze these opportunities. 1919 also saw the fulfillment of a long-standing Methodist goal: prohibition. The prohibition movement drew its greatest strength from the Methodist churches. In January 1919, that campaign succeeded when the 36th state ratified the 18th Amendment. Heady from this hard-won triumph, Methodist imagined all sorts of transformations were possible. The Centenary was instituted as a celebration of the church's missionary outreach and its acomplishments and an exhortation to the faithful to do more and contribute more to spread the Wesleyan message into the entire world. The Centenary sought to engage every Methodist believer in the missionary endeavor. |

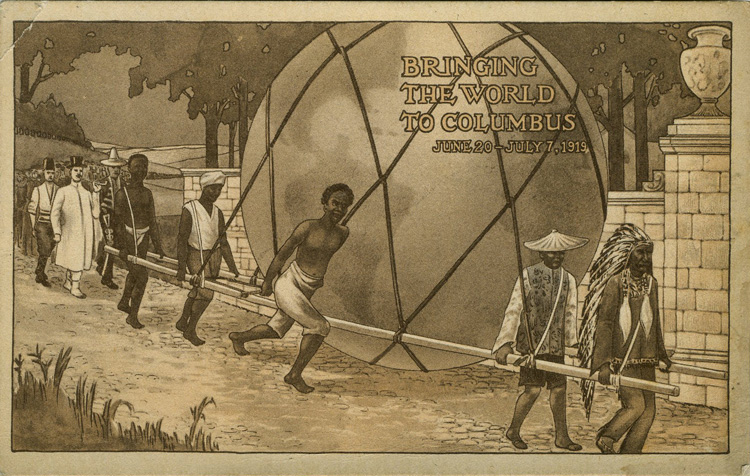

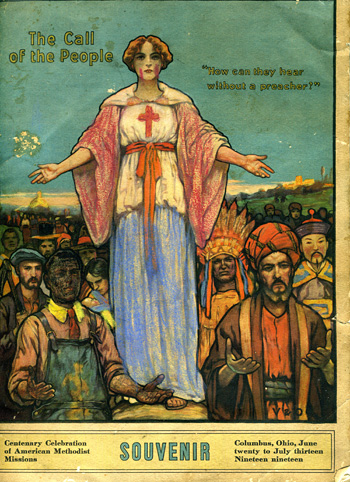

Cover of souvenir program from the Centenary. Text in picture reads: The Call of the People. How will they hear without a preacher? |

||

At the same time American Methodists were laboring to spread their faith abroad, new challenges were arising in their homeland. Entertainment was threatening the church's centrality in national life. The theater, motion pictures, amusement parks, automobile rides, professional sports, popular music, records, newspapers and magazines were laying claim to a larger and larger share of Americans' leisure hours. Especially among the young, Sunday School, sermons, and songfests weren't the draw they once were. The Centenary tried to pioneer new ways of holding onto the flock and evangelizing here at home. The churches had long decried and even banned entertainment. The Centenary tried to show how entertainment could be put in service of the church at home. Immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe was changing the character of American cities and shaking Methodism's hold. How was mainline American Protestantism to reach out to these new populations? Immigration of native-born Americans from The South to The North and from the country to the city posed additional problems. What would happen to the immigrant's faith once he had left the community that nutured it? The industrialism that drew these internal immigrants from their homes and industrial workers' struggles for social justice created still more difficulties for a religion with its roots in a homogeneous and comparatively egalitarian small-town America. Underlying the Centenary were assumptions of white supremacy, so deep rooted no organizer or attendee would have imagined questioning them. Colonialism and imperialism were never once questioned. The brutality, cruelty, exploitation, and injustice of colonial rule was never raised. That whites should rule over non-whites and tell them how to believe and live was central to the missionary enterprise celebrated by the Centenary. Beyond white supremacy, the supremacy of a certain version of whiteness was central. The beliefs, values, and culture of rural and small-town, native-born whites of more-or-less British ancestry were assumed inherently superior to those of foreigners and recent immigrants. The fight for Prohibition was a notable expression of this. Supprt for the US Government in all its endeavors was complete. American history was understood as the unfolding of divine will. Religious faith and patriotism were inseparable. To support one was to support the other. Mending wounds and building unity between Northern and Southern Methodists was emphasized. The evil of slavery was believed resolved by the Civil War and near universal racism wasn't an issue for attendees or organizers. Capitalism was likewise unquestioned. Men of wealth and property wrote the checks that built fancy churches, colleges, and seminaries. Capitalists funded missionary enterprises and charitable endeavors. Rank-and-file Methodists--small-town and rural farmers, merchants, tradesmen, and professionals--saw themselves as capitalists and entrepreneurs. The struggles of the urban industrial working classes and the attraction of trade unionism, socialism, and anarchism were alien to them. As deep and fundamental as these assumptions were there was one still deeper and more fundamental: patriatchy. Methodists supported women's suffrage but because it was essential to voting in Prohibition. In their wildest imaginings, no one dreamt of a role for women other than those tradition dictated.

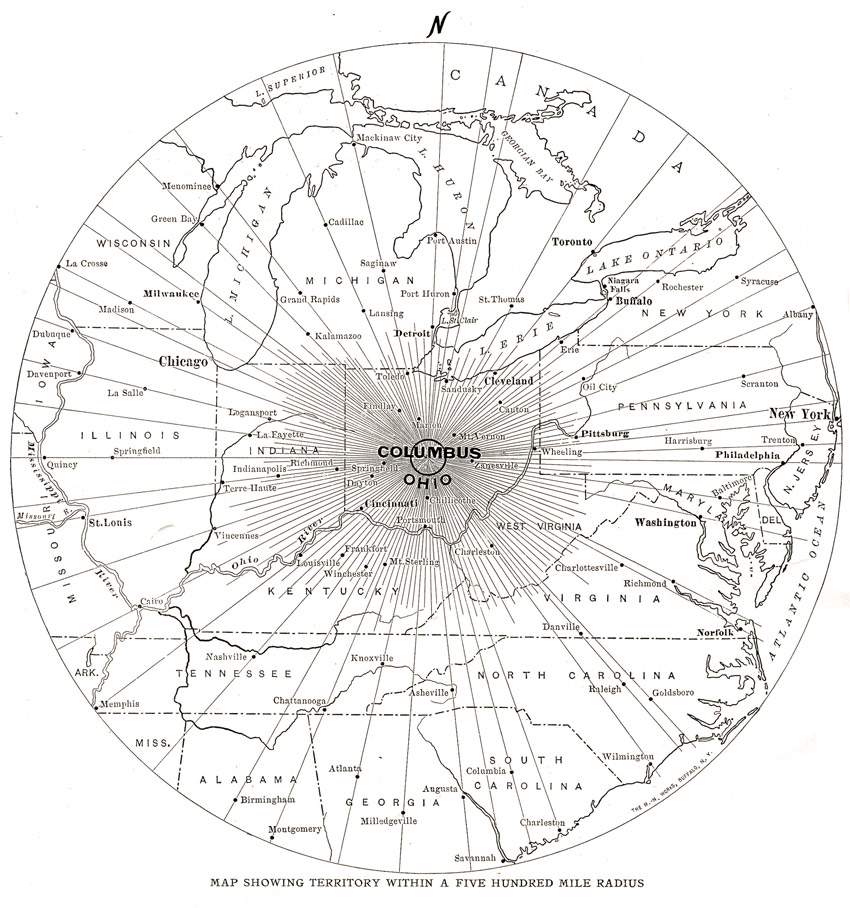

WHY COLUMBUS? The centenary was drawn to Columbus for the same reason so many other activities are drawn to the city: proximity. Columbus is centrally located. Most of the population of the United States in 1919 lived within 500 miles of Columbus. Eight of the ten largest cities in America in 1919 were within 500 miles of Columbus. Columbus was also a rail hub with good connectivity. Visitors could get here easily without too much travel time.

Another draw was that Ohio--and especially Columbus--was overwhelmingly Methodist. Methodists were by far the largest religious group in Ohio in 1920 and had been for a century. Prominent Methodist institutions--churches, seminaries, and colleges--were located in the state. Ohio was home to over 2,000 Methodist churches. Methodist churches in Ohio outnumbered those of Catholics and Presbyterians combined. Furthermore, Ohio had been a leader in the largely Methodist fight for Prohibition. The powerful Anti-Saloon League was based in Westerville, Ohio and led by Ohio men. A hundred thousand Methodists lived 2 hrs or less (by rail) from Columbus, 1 million Methodists lived less than 5 hours from Columbus, 3 million Methodists lived within a day's travel of Columbus--advantages no other considered city could boast of. The availability of the expansive Ohio State Fairgrounds and its many buildings secured the decision. That the fairgounds were in the city and close to streetcars, hotels, and restaurants sweetened the deal.

|

|||

|