358 E. 15th Ave., home of William H. Knauss. Photographed on Memorial Day 2015. |

|

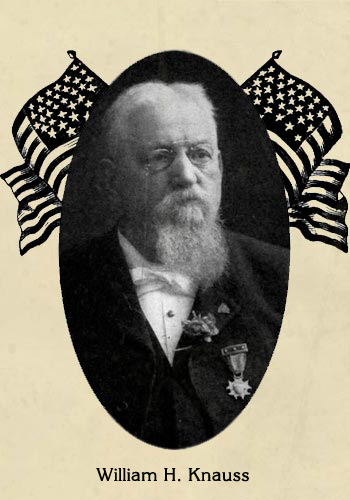

WILLIAM H. KNAUSS (1839-1912) Civil War veteran and binder of a nation's wounds A century ago, 358 E. 15th Ave. was the home of a noteworthy Columbus citizen and American patriot, William H. Knauss. Back in 1861, 22 year old William Knauss jumped at the opportunity to join the Union Army. Within weeks of the attack on Fort Sumter, Knauss was mustered into the 2nd New Jersey Infantry and off to war. The 2nd was on the field at Second Bull Run (August 1862) and Antietam (September 1862) but the soldiers saw their first real action at The Battle of Fredericksburg in December. The battle was a folly and a slaughter. Even though the battle's objective was already lost, foolish general Ambrose Burnside committed Union forces to repeated head-on assaults across an open field and up a hill in the face of dug-in and well-armed Confederate defenders. The result was a massacre. Union forces were mowed down by Confederate artillery and rifle fire. The senseless carnage was so great that Confederates reportedly begged the advancing Union troops to stop and save their lives. On the terrible day of December 13, 1862, over 1,200 Union soldiers were killed and more than 9,000 wounded. Among the wounded was William Knauss. A shell fragment struck him in the face. An inch to one side and he would have been killed. He bore an ugly scar from the wound for the rest of his life. |

|

|

|

Knauss carried something else away from the battle. For many years, W.H. nursed a hatred for the Rebels who had slaughtered his comrades and fired the shell that nearly ended his life. All that changed on a business trip to North Carolina in 1868. Knauss met a fellow veteran of Fredericksburg. The man was a Confederate and he had lost his leg in the fight. He and the Southerner became friends and shared their memories of that blood-soaked December day. Knauss came to see the Confederate soldiers as brothers who had suffered in the war just as he had. When he and his new friend parted, they pledged to each do their best to look after the other's comrades if ever they were in a position to help. In 1892, Knauss moved to Columbus. He and his son-in-law began buying, selling, and developing real estate. They were successful and built up considerable wealth. In 1893, Knauss built a fine home on E. 15th Ave., one of the first in the University District. One fateful day, business took Knauss out on Sullivant Ave. on the western edge of the city. There he saw the sad condition of the Camp Chase Cemetery. During the Civil War, Camp Chase had been a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederates. It stretched from W. Broad south to Sullivant and from Hague Avenue east to Demorest. At its peak, it had been home to nearly 10,000 Confederate prisoners-of-war. A smallpox epidemic in 1863 and overcrowding and a hard winter in 1864-65 took its toll on the inmates. When the war ended and the POWs returned home they left behind more than 2,000 dead. After the war’s end, the camp cemetery was forgotten. Bitterness among Union veterans and politicians made care of Confederate graves an unpopular cause. Weeds and briars grew high on the grounds. Wooden grave markers rotted away. Gophers and rabbits made their homes among the decaying monuments. Developers cast greedy eyes on the acreage and wondered how it might be converted to more profitable use. |

|

Knauss was appalled and began the project that would become his life’s work. He argued that the fallen husbands, sons, and brothers of Camp Chase deserved better. The war was over and North and South were reunited. All were Americans now and brothers:

He wrote to politicians, complained in letters to the editor, contacted Southern veterans associations, toured and lectured, raised funds, spent freely from his own pockets, and even put his own back to work in the cause of restoring the cemetery to a decent condition. In 1895, Knauss conducted the first Memorial Day ceremonies on the grounds with little more than his own family in attendance. His campaign was not a popular one in the North. Though the war was thirty years past, feelings still ran high. Union widows and orphans attacked him as a traitor. Survivors of the inhumane Southern prisoner-of-war camps asked how he could forget their suffering. Northern veterans' groups were openly hostile. Knauss lost business and received threats of violence and even death. |

Decoration Day ceremonies 1898 from Knauss' book The Story of Camp Chase (1906). |

His patriotism was questioned. An ad hoc committee formed among legislators at the Statehouse and demanded he present himself and give an account of his actions. He refused. They threatened him with dire consequences he did not cease his activities. Several times, guards had to be posted at the cemetery against threats of vandalism. Once, attackers threatened to destroy the place with dynamite. Despite this, Knauss persevered and his campaign bore fruit. The weeds and brush were cut and arrangements made to have the grounds cared for. Flowers and ornamental trees contributed by Southern states were planted. A solid stone wall was erected around the burying ground. Rotted or decaying wooden markers were replaced with stone ones. Each year, Knauss arranged a memorial service at the grounds on Memorial Day. Each year, the size of the audience in attendance grew. Each year, more local and state notables were willing to appear. In 1897, the mayor was in attendance. In 1900, the governor came and said a few words. In 1897, an inscribed boulder was placed there as a collective memorial. The text read "2,260 Confederate Veterans of the War 1861-1865 Buried in This Enclosure." In 1902, a memorial arch inscribed simply “Americans” was added as tribute to the fallen. |

|

|

|

After the dedication of the arch in 1902, an aging Knauss turned over preservation of the cemetery and organization of the annual memorial to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. He wasn't quite done though. His travels and encounters had made him something of an expert on the camp. In 1906, he published The Story of Camp Chase, the definitive history on the subject. Based on diaries, letters, and interviews with prisoners and guards, the book chronicles the story of life in the POW camp. It tells of the inmates' loneliness, hardships, privations, disease, escapes, attempted escapes, conspiracies, occasional moments of joy and fellowship, and the ever-present mud. The volume also records the history of Knauss' efforts to restore and preserve the burying ground. Knauss spent the rest of his years supporting various patriotic causes. It’s said he spent much of the remainder of his fortune providing free American flags to any school that wrote him to ask for one. In 1917, at the age of 77, Knauss died in his 15th Ave. home. He was buried in Greenlawn Cemetery beneath a monument commemorating his military service A few months earlier, Confederate Veteran magazine remembered Knauss thusly:

In 1922, the United Daughters of the Confederacy placed a plaque at the entrance to the cemetery honoring Knauss' memory In the 21st Century, Knauss' legacy is complicated. Knauss volunteeered and was greviously wounded in the fight to overthrow the South's racist regime. He marched to war to the strains of "John Brown's Body." Knauss' compassion for forgotten soldiers, rotting in unmarked graves, far from home, seems to come from a pure and good place. He saw the dead of Camp Chase as men not soldiers, as fellow victims of war. However, his deeds seem oblivious to the times. Though slavery had been abolished and citizenship granted to blacks, Southern terrorists stole their rights in the 1870s, enforced their subjugation with the lynch mob, and reenslaved blacks through mass incarceration and prison labor. The Southern veterans Knauss courted for support and lectured before were the architects of these crimes. The Daughters of the Confederacy who heaped accolades on Knauss were the chief architects of the Lost Cause mythology that denied the horrors of slavery and honored the monsters who killed thousands of Americans in its defense. However well-intentioned, Knauss' efforts served the rehabilitation of the satanic racist regime of the Confederacy. A bit worse for a century's wear, Knauss' home still stands on E. 15th Ave, in the University District. |

|

|

|